First Published: 20 June, 2022

There are several ways to consider who and what are stakeholders in both an organization and an organization’s projects. The “shareholder theory,” posited in the early 20th century by economist Milton Friedman, says that a company is beholden only to shareholders - that is, the company must make a profit for its shareholders.

Stakeholder theory was first described by Dr. F. Edward Freeman, a professor at the University of Virginia, in his landmark book, “Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach.” It suggests that shareholders are merely one of many stakeholders in a company. The stakeholder ecosystem, this theory says, involves anyone invested and involved in, or affected by, the company: employees, environmentalists near the company’s plants, vendors, governmental agencies, and more. Freeman’s theory suggests that a company’s real success lies in satisfying all its stakeholders, not just those who might profit from its stock.

In this article, we’ll explain stakeholder theory, and also talk to two leading global economists and philosophers on why it shapes a better and stronger company. We will also look at how individual projects may have an impact on a variety of types of stakeholders.

Edward Freeman’s stakeholder theory holds that a company’s stakeholders include just about anyone affected by the company and its workings. That view is in opposition to the long-held shareholder theory proposed by economist Milton Friedman that in capitalism, the only stakeholders a company should care about are its shareholders - and thus, its bottom line. Friedman’s view is that companies are compelled to make a profit, to satisfy their shareholders, and to continue positive growth.

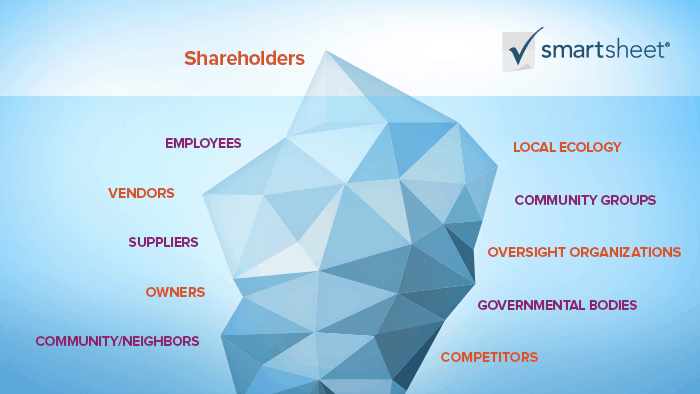

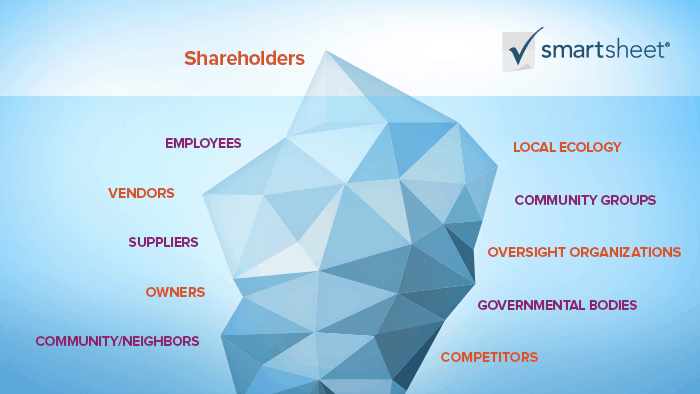

By contrast, Dr. Freeman suggests that a company’s stakeholders are "those groups without whose support the organization would cease to exist." These groups would include customers, employees, suppliers, political action groups, environmental groups, local communities, the media, financial institutions, governmental groups, and more. This view paints the corporate environment as an ecosystem of related groups, all of whom need to be considered and satisfied to keep the company healthy and successful in the longterm.

Dr. Freeman’s books describe how a healthy company never loses sight of everyone involved in its success. Stakeholder theory says that if it treats its employees badly, a company will eventually fail. If it forces its projects on communities to detrimental effects, the same would likely happen. “A company can’t ignore any of its stakeholders and truly succeed,” Dr. Freeman said in an interview. “There might be short-term profits, but as stakeholders become dissatisfied, and feel let down, the company cannot survive.”

Dr. Freeman’s books describe how a healthy company never loses sight of everyone involved in its success. Stakeholder theory says that if it treats its employees badly, a company will eventually fail. If it forces its projects on communities to detrimental effects, the same would likely happen. “A company can’t ignore any of its stakeholders and truly succeed,” Dr. Freeman said in an interview. “There might be short-term profits, but as stakeholders become dissatisfied, and feel let down, the company cannot survive.”

Economist Milton Friedman, whose work shaped much of 20th-century corporate America, was a believer in the free-market system and no government intervention. This belief helped shape his shareholder theory of capitalism: that a company’s sole responsibility is to make money for its shareholders.

Also called the “Friedman doctrine,” shareholder theory, outlined in Friedman’s book “Capitalism and Freedom,” states that a company has no real “social responsibility” to the public, since its only concern is to increase profits for the shareholders. The shareholders, in turn, would privately shoulder any social responsibility.

When Edward Freeman first published his book about stakeholder theory in 1984, it raised awareness of the relationships and the ripple-effect of a company and its many stakeholders.

It suggests that a company’s stakeholders include people like employees, customers, community members, competitors, vendors, contractors, and shareholders. Stakeholders could also be institutions, like banks, governmental bodies, oversight organizations, and others.

“If you think about it, it makes sense,” Freeman said in an interview. “All company stakeholders are interdependent. And a company creates value - or should, for its own success - for all of them.”

“If you can get all your stakeholders to swim or row in the same direction, you’ve got a company with momentum and real power,” Freeman says. “Saying that profits are the only important thing to a company is like saying, ‘Red blood cells are life.’ You need red blood cells to have life, but you need so much more.”

Stakeholder theory is even more important in the new global economy, Freeman notes. An organization needs to be mindful not only of those who hold stock in the company, but also of those who work in its stores, those who work and live near its factories, those who do business with it, and even of competitors, as the company may shape the landscape in its industry.

“Even some older companies like Unilever are re-inventing themselves to use stakeholder theory with very strong results,” Freeman says. And the results if a company doesn’t subscribe to stakeholder theory? “Enron,” he says, of the energy company that was brought down by corruption and other scandals in the early 2000s.

Let’s consider a hypothetical company that builds condos in an American city. That company has gone public, so its shareholders are eager to see a rise in the value of their stock. Under stakeholder theory, however, those shareholders could be joined by several other types of stakeholders, each with its own interests relative to the company. Here are a few possible stakeholders with interest in this company and its projects:

Employees: The employees want to be treated and compensated fairly, and work reasonable hours. If the company underpays the employees, or gives them lengthy and difficult work shifts, the employee attitude and buy-in in the company is going to erode. There will be turnover, bad word-of-mouth among the potential workforce in the area, and a weakened company.

This is by no means a complete list, but as you start to think of your company and its projects in terms of the full ecosystem of potential stakeholders, you can see how far-reaching your impact can be. Some will have a financial interest in your project. Some will have an emotional interest. Many may have both. And stakeholder theory holds that all these stakeholders, as well as their interests, are critical to your project’s success.

Craig McDonald, Professor Emeritus of Informatics at the University of Canberra in Australia, has written extensively on stakeholder theory, and on how business ethics can shape the future success of a company.

Professor McDonald says his view is simple. “If you value life in the future, you should preserve the environment by addressing pollution, using sustainable extraction from the biosphere, etc…Presumably, you act in a way that you hope will express your values, and produce an outcome that makes you happy.”

In other words, he says, corporate responsibility and business ethics don’t need their own special focus inside the company, as long as the company practices true stakeholder theory for all its stakeholders, from suppliers and employees to factory workers and environmentalists.

“Of course, it doesn't always work out this way,” McDonald says, “maybe because we don't know what our real values are until we are in a position that tests them, or maybe… things went pear-shaped, despite our good will…The bottom line is, figure out what your values are, what your context is, what the consequences of your actions will be. Then decide what to do in a knowledgeable and responsible manner.”

In today’s global economy, Professor McDonald says, consumers should be prepared to pay the real price for goods. He speaks of a hypothetical manufacturer of a popular product, which is sold around the world, though primarily in the Americas and Europe. The product is manufactured in Asia, where the employees are underpaid, and deal with tough working conditions. Additionally, the plants may be polluting the local environment.

In today’s global economy, Professor McDonald says, consumers should be prepared to pay the real price for goods. He speaks of a hypothetical manufacturer of a popular product, which is sold around the world, though primarily in the Americas and Europe. The product is manufactured in Asia, where the employees are underpaid, and deal with tough working conditions. Additionally, the plants may be polluting the local environment.

“This company,” Professor McDonald says, “should be brought to account by international law. Its directors and executives should be put to work to repair the damage they have done, and improve the lot of all concerned. And If the consumers didn't know about the real cost of their product, they should be told, and should pay the real price. If they did know and didn't care, they should join the directors [in helping repair the damage]. The market needs to be restructured to ensure that we assess the real economic cost of products and services.”

When you can use the opinions and influence of all your stakeholders to help shape your project, you and the project will be much better positioned for success. The benefits can shape the perception of your project and your company, not only with all of your extended stakeholders, but with the rest of the world.

Edward Freeman says that organizations, especially corporations, need to stop thinking of the word “ethics” in only a negative fashion. “It’s a word typically done in a negative light, as in, ‘that company has bad ethics, or isn’t behaving ethically.’ Instead, if we are practicing stakeholder theory, we need to shine a light on ethics when they are positive.” This means being transparent about how the company has considered the needs and interests of employees, suppliers, factory workers, local neighbors, and everyone else.

Creating this healthy ecosystem, Freeman says, “is needed for the company to truly succeed in the longterm. If a company cuts corners with any of these stakeholders, it isn’t going to work out over the long haul.”

The effective use of stakeholder theory also yields good public relations. If the condo-building company builds a park for the local neighbors, and cleans up a nearby creek that’s an important watershed in the area, the entire city will have a much more favorable view of the company, paving the way for long-term future success.

Once you’ve identified your extended group of stakeholders and their biggest needs, interests, etc., you can also begin to draft a communications plan.

In the case of the condo development, it may be useful to identify a neighborhood liaison, for example, an on-site employee who can periodically visit the neighbors, hold meetings, etc., to ensure all nearby residents feel they are being heard.

Professor Edward Freeman is a leading expert in stakeholder theory, and has written many books on the topic. He is a professor at the Darden School of Business at the University of Virginia. Learn more about Freeman:

Other sources include a popular textbook on the topic, “Business and Society: Ethics, Sustainability, and Stakeholder Management,” by Archie B. Carroll and Ann K. Buchholz, first published in 2014.

Professor Craig McDonald teaches at the University of Canberra in Australia, in the study of informatics, which focuses on the interconnectivity of business, technology, and other areas. Additionally, most business schools now teach stakeholder theory, sometimes in business ethics courses.

Empower your people to go above and beyond with a flexible platform designed to match the needs of your team — and adapt as those needs change.

The Smartsheet platform makes it easy to plan, capture, manage, and report on work from anywhere, helping your team be more effective and get more done. Report on key metrics and get real-time visibility into work as it happens with roll-up reports, dashboards, and automated workflows built to keep your team connected and informed.

When teams have clarity into the work getting done, there’s no telling how much more they can accomplish in the same amount of time.

Written by Becky Simon.

First published on Smartsheet website November 23 2016 (Updated March 14 2022)

Category

Contact us if you have any suggestions on resources you would like to see more of, or if you have something you think would benefit our members.

Get in TouchSign up to receive updates on events, training and more from the MA.