First Published: 06 August, 2019

We seem to be living through a time of changing rules when it comes to Experience. The town crier is walking the streets, ringing a loud and insistent bell and shouting “the old experience is dead, long live the new experience.”

“There must be some kind of way outta here

Said the joker to the thief

There's too much confusion

I can't get no relief”

(All along the watchtower – Bob Dylan)

The trouble is that there appears to be great uncertainty about the agenda of this new ruler. Maybe we need to take some time to understand the agenda? Sadly, the course of human history has now shown us that a lack of understanding doesn’t stop the invention of the one true answer – or the creation of several competing and often contradictory answers. The cacophony of differing viewpoints around Brexit gives ample testimony to the ability for humans to develop competing answers and high passion around a poorly formed question.

When you start to look into the technology landscape and the pro-am punditry in places like LinkedIn, it starts to look as though there is a technological version of the one true answer – what you need is “Digital Transformation”, written as a special noun so you know it’s important. So, there we are marching the streets shouting, “What do we want? – Digital Transformation… When do we want it? - Now!” That’s great, but sometimes the message is high on feeling but low in reasoning and rational advice. In this post, I hope to provide you with some sound reasoning and avoid straight out rhetoric.

I am, by education and inclination, driven by philosophical concerns and first principles rationality. I like to try and unpick the why, how, and in what order aspects of prescriptive injunctions. I subscribe to the theory that better questions lead to better outcomes. I’m not going to try and unpack all the why, how and in what order questions that swirl around the injunction to “do” Digital Transformation. However, I will try and address the wider questions around improved experience as I believe it is one of the fundamental factors and expected outcomes of digital transformation.

Why do we need to change experience?

Not long ago, the world of the organisation and the world of the user were separated by a transactional divide. The model was one of an organisation “doing to” and the user “getting from” via a set of constrained physical-world interactions and the slow exchange of letters and forms. User experience was just that – an experience. It wasn’t designed, it wasn’t treated as a journey or a relationship, it was simply the input and output exchange mechanism for the packets of information or physical products between provider and consumer.

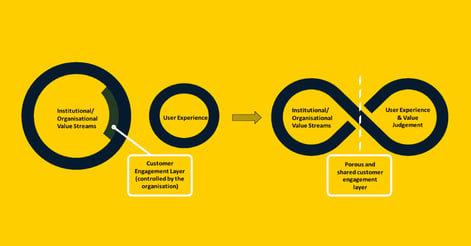

Figure 1: The changing nature of user experience

Intergen has witnessed and been directly involved in the transformation of this state of affairs into a fundamentally different model. Organisations are evolving to a “doing for” model and users are “working with” those organisations. One of the primary catalysts for this change is the adoption of digital technology and the rising user expectations around digital services. Users and organisations are no longer separated by a technology or infrastructure divide. The power balance has been disrupted and the castle ramparts of traditional customer engagement have been irrevocably breached.

The “fourth wall” between users and organisations has been broken - both by disruptive new market entrants and by users themselves. You can’t pretend that your customers aren’t there in the theatre with you – they are, and they’re savvy, increasingly well informed and they understand the stagecraft you use. If you don’t give them what they want and what they need then they’re going to go elsewhere. There are plenty of other shows in town and they know where to find them. Better get used to the new normal!

Getting to know you

“Getting to know you

Getting to know all about you

Getting to like you

Getting to hope you like me”

(The King and I – Rodgers and Hammerstein)

I’m sure Rodgers and Hammerstein didn’t realise that they were predicting one of the fundamental strategic challenges to 21st-century business survival when they were writing The King and I, but they were not far off the mark. Getting to know your customers/users/stakeholders in a detailed and dynamic way and creating brand affection form the bedrock to designing relevant experiences.

So, what is the problem? Why aren’t we all delivering amazing experiences to our users or always enjoying awesome experiences as customers of other organisations? I’d like to offer up two inter-related ideas that highlight why this is more challenging than it first appears.

Where does the time go?

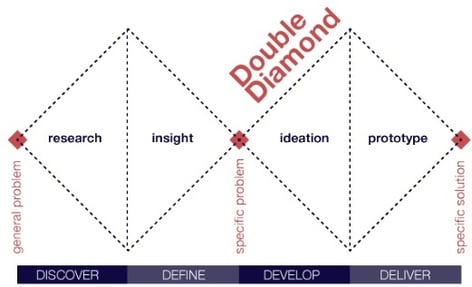

If we want to create amazing experience, wouldn’t it be useful if there were processes we could follow that had been tried and tested? The good news is that there are! One of these is the “double diamond” process developed by the British Design Council. It’s well accepted and forms the basis of numerous design thinking workshops and hackathons. It’s an iterative process to get from a generalised problem to a specific solution.

Figure 2: The Double Diamond of Design Thinking

It’s the double bit that’s the key to this and the Design Council states that one of the greatest mistakes lies in omitting the left-hand diamond and ending up solving the wrong problem (or designing the wrong experience). This ties back to the title of the blog post – we contend that you need to spend quality time in discovery and define phases around understanding users in order to guide the development and delivery of the right experiences.

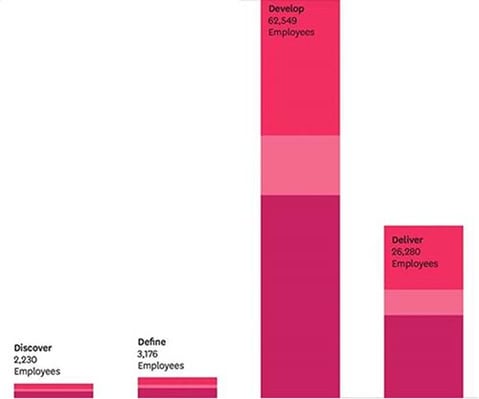

The evidence suggests that as a nation we don’t do this. Designco (a collaboration between several large universities, NZTE and the Designers Institute) commissioned PWC to conduct some research into the value of design to the NZ market. As part of that analysis, PWC looked at the resource investment within NZ across the four phases of the double diamond.

Figure 3: Investment in Double Diamond Design in NZ (Source: PWC)

To me, that looks like you’ve got a lot of people developing and delivering to the second part of the process, but it begs a couple of significant questions. First, who are they building things for? Secondly, how did they qualify the problems in order to validate the significant investment of cost, time and effort implied in by this diagram?

The analogy I like to use to explain why this is a problem is to think of this as developing a tool. The investment profile suggests that what we’d end up with is a tool where all the mass is in the end of the tool. More a sledgehammer than a crowbar or a screwdriver. Hammers may not be elegant but can be very effective – but you need to be very sure of what you are trying to hit. The challenge of deploying a sledgehammer approach in improving user experience is that it lacks subtlety and there are significant dangers of causing major damage if you hit the wrong thing. Therefore, you really, really need to understand your user exceptionally well, which is best achieved by investment in discover and define activities – Doh! – we don’t do that, so you can see the dilemma.

“Don’t worry. We’ve got our best people working on this. They really understand the problem…”

This is the obvious answer to the issue. “Sure, we understand that there’s some value in the first half of the diamond, but the problem domain is really complicated so we’ve got our best and brightest working on the development.”

Herein lies the second and inter-related problem. People aren’t just complicated; they’re also complex and are diverse. Getting to know your users isn’t the same as getting to know a programming language or getting to understand a complicated scheduling algorithm. Direct cause and effect don’t necessarily apply. We are in the land of neuroscience, dispositional behaviour, ancient brain vs modern brain thinking and behavioural economics.

The reality of user experience is that it inherently eludes logical analysis. This slippery setting is besieged on all sides by the phenomenon of cognitive bias. Wikipedia defines cognitive bias as “a systematic pattern of deviation from norm or rationality in judgment. Individuals create their own "subjective social reality" from their perception of the input”.

The challenge is multi-pronged, Wikipedia lists over 180 different forms of cognitive bias that can contribute to the multiple subjective realities of user experience. The diagram below is an attempt to categorise these biases into a taxonomy. The irony is that the effort to do that is probably an example of the cognitive biases of the creator to cope with too much information.

It’s also a multi-sided problem, as cognitive biases exist not just with users but also with the developers and deliverers of user experience. When you have your subject matter expert designing the user experience for your users you will also have that expert’s biases front and centre in the process.

Figure 4: The Cognitive Bias Codex

It’s not all bad news though. Some of these biases are inherently useful in helping to design experiences. For example, if you know about the serial position effect (the tendency of a person to recall the first and last items in a series best and the middle items worst) you can think about where to position the key things you want remembered within the experience.

What it does mean though is that your best and brightest might not be the best candidates for creating user experience because of their very expertise. Experiences developed for an idealised user by an expert are great in theory. It’s just those messy and unpredictable human beings that break things! This prevailing model for design will work brilliantly when we are designing for logic-driven robots but perhaps not for the present.

And in conclusion

So, what is the closing argument? The things that due to cognitive bias you’ll probably remember better than the middle of this post. It’s this:

This blog is part of the #cxreimagine series. For more experts' insights, clients' experiences and to download the whitepaper, click here.

Contact us if you have any suggestions on resources you would like to see more of, or if you have something you think would benefit our members.

Get in TouchSign up to receive updates on events, training and more from the MA.